Fueled by this approach, Venegas has been one of many local stakeholders loudly voicing his support of study findings from the Southwest Detroit Business Association (SDBA) and local think tank Detroit Future City (DFC).

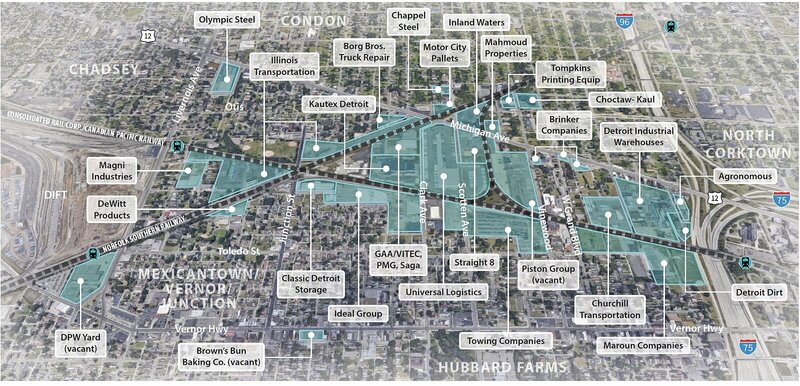

Initiated by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) Detroit, the recently released Exploring Opportunities for Equitable Development in a Southwest Detroit Industrial District delves into how community-based organizations can use equitable development strategies to incorporate industrial districts for economic development. In particular, the focus was on the industrial zoned properties located near the W. Michigan Ave. and Clark St. corridor (bounded by W. Michigan Ave., Livernois St., W. Vernor Hwy. and I-96/I-75).

A Detroit Future City report released in 2017 identified that there are over 900 vacant industrial sites in Detroit, many of which are embedded in residential neighborhoods. Tom Goddeeris, DFC’s COO, explains that the premise of the newer study was to look at how older industrial areas that are embedded within Southwest Detroit neighborhoods could be put into productive use to serve the community.

“The pattern of development in Detroit was that industry followed the railroad tracks and crisscrossed the city, and there was a time when there were big employers in the city and people would walk from their home to the factory,” Goddeeris says. “In Southwest Detroit this is very obvious because there are cases where people actually live right across the street from an industrial area. There is a legacy of industry that’s really woven into the fabric of the city.”

The more recent study offers a framework for approaching the reuse of industrial sites that stresses the need for low-income and under-resourced communities to have a say in the decisions that shape their neighborhoods and impact their quality of life. Some of the recommended strategies include exploring ways to attract and retain businesses that offer good employment opportunities to local residents, prioritizing local ownership and businesses owned by women and people of color, employing steps to mitigate negative environmental impacts, and the incorporation of beautification efforts, green space and other buffers between polluting facilities and residential areas.

These action steps are imperative and impactful, says Venegas, whose family came to the United States from Mexico 100 years ago. His father, Frank Venegas, started the company in 1979, then named Ideal Steel & Builders’ Supplies. The business gradually expanded from a single company into several companies, and eventually set up a shop in Southwest Detroit in the early 1990s where the Venegas have long-standing family ties. Today, Ideal Group employs 1,000 people, and several hundred work locally.

Every year the company spearheads about 5,000 hours of local volunteer events and community service, including supporting kids’ groups and local schools. They’ve also formed programs that have mobilized residents and other businesses to clean up trash, and created an urban garden that boasts 250 above-ground planters. Volunteers and local residents who help out can take home fresh fruits and vegetable beds to feed themselves and their families. Many years ago, Ideal Group also hired 60 people who were either former or active gang members, many of whom were nurtured into advanced roles and who are still currently working for the company.

“We acquired a facility with about 180,000 square feet of manufacturing space, but when we moved in we knew we needed to look beyond that space. It didn’t take long for us to see that the community had a lot of needs beyond business needs,” Venegas says. “Creating opportunities and caring for the community in ways that allow for everyone to be prosperous is just the right thing to do, and if we can all work together we can create a great future for Southwest Detroit.”

The Ideal Group’s trajectory has been personally inspiring to Greg Mangan, SDBA’s real estate advocate. He says that they are proof that industrial sites can be turned into assets that can improve the look and feel of the streetscapes and properties in the area.

“We saw an opportunity to work with LISC and Detroit Future City and community stakeholders to look at this area that is a major job center and a kind of center for businesses that are mostly in the manufacturing distribution realm,” he says. “However, there’s always a push-pull between creating jobs and economic development, and the sometimes negative, environmental factors that come from industrial sites.”

Mangan underscores that the work of SDBA is emphasizing the quality of jobs and types of businesses that could be developed within these older industrial areas. They don’t have to be heavy industrial jobs or polluting jobs. They could be light manufacturing jobs and various other, cleaner industries, which could open up employment opportunities for folks who don’t have an educational degree or specific technical training.

“There’s an emphasis in the report on locally-owned, small-scale manufacturers as a strategy for redeveloping these industrial areas that can provide good jobs, while not having a negative impact,” he says.

Mangan also explains that residents have real concerns about the smells coming from industrial businesses. The vibrations, diesel exhaust, and brake dust from trucks come past their houses and community stores, often along narrow streets where trucks don’t fit.

“Right now it’s about finding a way to do this redevelopment deliberately and gently so that we can position industrial companies in neighborhoods to create opportunities that will improve residents’ lives,” he says. “The impetus is on us and other community development organizations like us to attract more job creators to the neighborhood who have that shared vision.”

Mangan points to a key strategy outlined in the Industrial District Study that recommended hiring an SDBA district manager to serve as a business connector, district marketer, and equitable development advocate. Last October, Juan Guttierez stepped into the role and one of the things he has been working diligently on is trying to identify different industrial and light industrial manufacturing businesses that can come into the area.

“If a company has a small operation and they may be ready to look for a space to expand their operations, then I try to meet with them and act as an incubator for that growth so they can expand to the next level,” Guttierez says. “I’m also dialoguing with both business owners and residents who have legacy in the area to find out what they need since they are on the frontlines of being affected.”

The SDBA is trying to develop a tax increment financing (TIF) strategy that could generate funds to pay for green stormwater infrastructure or other improvements in the district. A TIF district would capture the increase in property taxes due to development and reinvest those funds in district improvements to spur further economic growth.

Now that strategies have been laid out, the time for action is right now, says LISC-Detroit’s executive director Camille Walker Banks. Referring to LISC’s mission to assist communities – particularly those that are underserved – with their community development efforts, she feels strongly that leveraging everyone’s cooperation and understanding will allow the Southwest Detroit community to remain vibrant and resilient.

“There are some systemic gaps in the way in which we administer our programming in this area. The study, in this community, at this time, can really help to galvanize all stakeholders so that we can create this industrial district that is critically located,” she says. “There is renewed interest in Southwest Detroit and new players are welcome. The Ford Innovation Center is coming into play, so now is the perfect time for a framework that we can put into action.”

LISC made an investment into the study with the goal to engage the residents and the businesses and Walker Banks wants to encourage continued involvement and momentum. Residents and businesses should reach out to the SDBA with their suggestions and concerns and ask how they can get involved in the community’s prosperity.

“This is a unique time in our history. We’ve never had such a level of cooperation locally and federally before,” she says. “In five or 10 years down the road we can really make some good things happen, so we want everyone off the sidelines now that we have a framework of what needs to be done.

Jaishree Drepaul-Bruder is a freelance writer and editor currently based in Ann Arbor. She can be reached at jaishreeedit@gmail.com.